"On the 28th of August, 1749, at mid-day, as the clock struck twelve, I came into the world, at Frankfort-on-the-Main. My horoscope was propitious: the Sun stood in the sign of Virgo, and had culminated for the day; Jupiter and Venus looked on him with a friendly eye, and Mercury not adversely; while Saturn and Mars kept themselves indifferent; the Moon alone, just full, exerted the power of her reflection all the more, as she had then reached her planetary hour. She opposed herself, therefore, to my birth, which could not be accomplished until this hour was passed.

These good aspects, which the astrologers managed subsequently to reckon very auspicious for me, may have been the causes of my preservation; for, through the fault of the midwife, I came into the world as dead, and only after various efforts was I enabled to see the light."

The Autobiography of Goethe, 'From my Life: Poetry and Truth', 1811

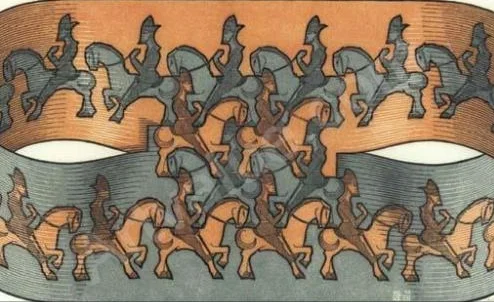

In a curious passage in his optical writings Goethe maintained that the astrologers were wrong to ascribe evil results to the presence of Sun and Moon in opposite corners of the heavens. "The full moon does not stand opposed in enmity to the sun but sweetly returns the light it lent to her; it is Artemis, gazing in love and longing at her brother." In his view the apparent opposites need not be in conflict. ('Paradoxer Seitenblick auf die Astrologie')

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)